Saturday, July 31, 2021

Formas aristotélicas y leyes de la naturaleza

Thursday, July 29, 2021

God's vision of reality

Consider the simple theory of visual sensation on which for me to have a visual sensation as of y is for x to stand in a “vision relation” to y, with the relation being external to x so that x is no different intrinsically when x has a visual sensation as of a red cube and when x does not.

We know that this simple theory is false of us for the obvious reason that we suffer from visual hallucinations or illusions: there are cases where we have a visual sensation as of a red cube in the absence of a red cube. Our best explanation of visual misperception is that visual sensation is mediated by an internal state of ours that can occur in the absence of the apparently visually sensed object. Thus, we have internal modifications—accidents—of visual perception.

But now consider what I think of as the biggest objection to the doctrine of divine simplicity: God’s knowledge of contingent facts. This objection holds that God must be internally different in worlds where what he knows is different, or at least sufficiently different. This objection is based on the intuition that knowledge is written into the knower, that it is an intrinsic qualification of the knower.

Let’s, however, think what a perfect knower’s knowledge would be like. My knowledge divides into the dispositional and the occurrent: I dispositionally know my multiplication table, but at most one fact from that table is occurrent at any given time. It is clear that having merely dispositional knowledge is not the perfection of knowledge. A perfect knower would know all reality occurrently at once. Moreover, my knowledge varies in vividness. Some things, like perhaps the fundamental theorem of algebra, I know “theoretically” (in the modern sense of the word, not the etymological one) and “discursively”, and some facts—such as my visual knowledge of the screen in front of me—are vividly present to my mind. The vivid knowledge is more perfect, so we would expect a perfect knower to know all reality occurrently at once in the liveliest and most vivid way, more like in a vision of reality than in a discursive mental representation.

Let’s go back to the simple theory of visual sensation. Our reason for rejecting that theory in our own case was that it did not accord with the fact that humans are subject to visual misperception. But suppose that we never misperceived. Then we could easily believe the simple theory, at least until we learned a bit more about the contingent causal processes behind our visual processing.

Thus, the reason for rejecting the simple theory in our case was our imperfection. But this leaves open the possibility that something like the simple theory could hold for the vision-like knowledge of reality that a perfect knower would have. Such a knower might not have any internal state “mirroring” reality, but might simply have reality related to it in a relation of being-known which is external on the knower’s side. In the case of a perfect knower, we have no need to account for a possibility of misperception. Thus, the perfect knower may know me simply by having me be related to it by a relation of being-known, a relation external to the knower.

Objection 1: How do we account for God’s knowledge of absences, such as his knowledge that there are no unicorns? This cannot be accounted for by a relation between God and the absence of unicorns, since there is no such thing as the absence of unicorns.

Response: In the case of an imperfect knower, absence of knowledge is not knowledge of absence, since there is always the possibility of mere ignorance. But perhaps in the case of a perfect knower, knowledge of absence is constituted by absence of knowledge.

Objection 2: This account makes the perfect knower’s “knowledge” too different from ours for us to use the same word “knowledge” for both.

Response 1: We have good reason to think that all words applied to us and the perfect being to be applied merely analogously. A perfect being would be radically different from us.

Response 2: While the simple theory is false of us, given dualism we may have a somewhat more complex theory that is not so different from what I said about God. We have significant empirical reason to think that the brain is modified by our visual experiences, and that our visual experience is in some way determined by an internal state of the brain. However, if we are dualists, we will not think that the internal state of the brain is sufficient to produce a visual experience. There could be zombies with brains in the same state that we are in when we are seeing a red cube, but who do not see.

We can now give two different dualist theories about how I come to see a red cube. Both theories suppose an internal red-cube-mirroring state rb of my brain. On the causal theory, the state rb then causes an internal state rs of the soul (=mind) which mirrors the relevant features of rb, and I have a red-cube experience precisely in virtue of my soul hosting rs. But the causal theory is not the only option for the dualist. There is also a relational theory, on which my red-cube experience is constituted by my soul’s standing in an external relation to the brain state rb.

The two theories yield different predictions as to possibilities. On the causal theory, it is possible for me to have a red-cube experience in a world where God and my soul (and my soul’s states and me-constituted-by-my-soul) are all that exists—all that’s needed is for God to miraculously cause rs in my soul in the absence of rb. On the relational theory, on the other hand, I can only have a red-cube experience when my soul stands in a certain external relation to a brain state, and in that God-and-my-soul world, there are no brain states.

The causal theory of our visual perception is indeed very different from the external-relation theory of divine knowledge. The relational theory, however, is more analogous. The main difference is that our visual experiences come not from our mind’s direct relation to the external world, but from our mind’s (=soul’s) direct relation to a representing brain state. And that is very much a difference we would expect given our imperfection and God’s perfection: we would expect a perfect knower’s knowledge to be unmediated.

We have reason independent of divine simplicity not to opt for the causal theory in the case of God. First, on the causal theory, we seem to have great power over God: every movement of ours causes an effect in God. That seems to violate divine aseity. Second, the causal theory in the case of God seems to lead to a nasty infinite causal chain: if God’s vision-like knowledge of y is caused by y, then we would expect that God’s knowledge of his knowledge of y is caused by his knowledge of y, which leads to an infinite causal chain. Moreover, God would know every item in this infinite sequence, which leads to a second causal chain (God’s knowledge of God’s knowledge of … the first chain). This would violate causal finitism, besides seeming simply wrong.

Do we have independent reason to opt for the causal over the relational theory in our case, or perhaps the other way around? I don’t know. Until today, I assumed the causal theory to be correct. But the relational theory makes for a more intimate connection between the soul and brain, and this is somehow appealing.

Monday, July 26, 2021

Material and formal mortal sin, and an insidious form of scrupulosity

This post is aimed primarily at Catholic readers, and especially Catholic readers given to a certain mode of scrupulosity (a disorder where one is unduly and irrationally worried about one’s sinfulness) I will describe further on down. I will say a little about the distinction between material and formal sin, then discuss a special form of scrupulosity that is enabled by knowing the distinction, and end with some philosophical considerations that should help defuse this form of scrupulosity.

Background:

The Catholic tradition distinguishes material and formal sin. Material sin is an action that is objectively in itself against the moral law. Formal sin, on the other hand, is an action insofar as one is morally culpable for it. Formal sin requires that one believe the action to be wrong and that one be sufficiently free in performing the action. Talking of something as material sin, or material sin of a certain sort, is talking of the act in itself. Talking of it as formal sin, or a formal sin of a certain sort, is talking of the relation between the agent and the act.

One can have material sin without formal sin: if in a very difficult medical ethics case, a doctor is told by a panel of otherwise trustworthy bioethicists that an operation is permitted, and performs the operation, and it turns out the bioethicists were wrong, the doctor has committed a material sin, but is unlikely to be guilty of formal sin.

The distinction can also be used not simply to remove responsibility but to reduce it. The Catholic tradition distinguishes mortal sin, which separates one from God by a definitive (but forgiveable, since God’s grace is immense) act of rejection, from venial sin, which does not definitively reject God. Given this, you can have mortal material sin which is not formally mortal. In such a case, you might not be clear enough on the grave wrongness of the action or you might be insufficiently free for the sin to be formally mortal, although you have enough clarity and enough freedom for formal venial sin.

A form of scrupulosity:

At the same time, logically speaking, things can go in the other direction. You can have material sin without formal sin. If the difficult medical operation is in fact permissible, but the trustworthy bioethicists tell the doctor that it is wrong, and the doctor performs it while believing it to be wrong, the doctor commits a formal sin without a material sin.

Similarly, it should be logically possible to have a sin that is materially venially sinful but which is formally mortally sinful because the agent misjudges the act as much worse than it is.

In my late teens and 20s, I suffered a lot from scrupulosity: I was constantly afraid that I had committed a mortal sin, in a way that was disproportionate to my actual moral failings (which I had plenty of, but mainly they weren’t the ones I was scrupulous about). And the possibility of a materially venially sinful act that is formally mortally sinful worried me a lot. I would say to myself things like: “Granted, on reflection, this was not objectively a mortal sin, and maybe not even a sin at all, but maybe at the time I thought it was grave, and so I was formally mortally sinning.” And I would engage in fruitless and agonizing soul-searching to figure out what it was that I was thinking when I was engaging in the act. I know I am not alone in suffering from this.

But even though it is logically possible to have a formally mortal sin that is materially venial, it is a striking historical fact that the Catholic tradition typically uses the formal-material distinction to excuse rather than to accuse, to the point where one fairly recent writer in a very helpful piece on scrupulosity actually writes that it is impossible to have the materially venial but formally mortal combination.

I thought about this, and realized that there is actually an asymmetry between using the formal-material distinction to lower responsibility and using it to boost responsibility. Here it is. Cases where a materially mortal sin is formally venial due to the agent’s error are easy to get given our individual and communal fallenness. All that’s needed is that the agent have enough considerations—say, coming from errors circulating in the community—against the thesis that the act is gravely wrong to induce sufficient doubt to make the action as done by the agent no longer be a definitive rejection of God.

But cases where a materially venial sin becomes formally mortal due to the agent’s error require that the agent definitely see the action as wrong. And that requires a more thoroughgoing kind of epistemic malfunction. It’s not enough that error induce sufficient doubt—that’s quite easy, hence the commonality of the responsibility-reducing case—but the error has to sufficiently silence the truth to make the agent definitely believe the erroneous thing. For without definite belief that the action is gravely wrong we do not have formally mortal sin.

Imagine that Bob is committing gluttony by eating one more potato than he should, and due to some error—perhaps grounded in an eating disorder—he starts worrying that eating this potato is a mortally sinful case of gluttony, but he continues eating nonetheless. But here is something else that is likely: unless Bob is very far gone down the path of error, he likely has a bit of common sense testifying in him that eating an extra potato is not a serious matter. On the one hand, then, he has error pulling him to think that it is mortally sinful to eat the potato, but on the other hand, he has common sense. The result is very likely to be a divided mind, rather than a mind definitely believing that the action is mortally sinful, and hence it is very unlikely that the action be formally a mortal sin.

In other words, it is easy to muddy the waters enough to reduce responsibility, but it is a lot harder to come to the kind of definite erroneous belief that would be required to increase responsibility.

And a fortiori it is even harder to have a case where an action isn’t materially sinful at all but due to error it becomes formally mortally sinful. Again I think such cases are possible, but I expect they are quite rare.

Finally, I would think that the rare cases where the formal-material distinction functions to raise responsibility are going to be even rarer in Catholics. For Catholics not only have conscience, but they have the Church’s guidance, and so it is even harder for them to be definitely mistaken.

Divine simplicity and knowledge of contingent truth

I think the hardest problem for divine simplicity is the problem of God’s contingent beliefs. In our world, God believes there are horses. In a horseless world, God doesn’t believe there are horses. Yet according to divine simplicity, God has the same intrinsic features in both the horsey and the horseless worlds.

There is only one thing the defender of simplicity can say: God’s contingent beliefs are not intrinsic features of God. The difficult task is to make this claim easier to believe.

It’s worth noting that our beliefs are partly extrinsic. Consider a world just like ours, but where a mischievous alien did some genetic modification work to make cows that look and behave just like horses to the eyes of humans before modern science, and where humans thought and talked about them just as in our world they talked about horses. If a 14th century Englishman in the fake-horse world sincerely said he believed he owned a “horse”, he would be expressing a different belief from a 14th century Englishman in our world who uttered the same sounds, since “horse” in the fake-horse world doesn’t refer to horses but to genetically modified cows. Their beliefs about rideable animals would be different, but inside their minds, intrinsically, there need be no difference between their thought processes.

But it is difficult to stretch this story to the case of God, since it relies on observational limitations. Moreover, it is hard to extend the story to more major differences. If instead of fake horses, the alien produced tauntauns, no doubt the minds of the people in that world would be intrinsically different in thinking about riding tauntauns from our minds when think about riding horses (even if accidentally their English speakers used “horse” to denote a tauntaun).

While our beliefs are partly extrinsic, God’s contingent beliefs are radically extrinsic according to divine simplicity. There are no intrinsic differences in God no matter how radical the differences in belief are.

This feels hard to accept. Still, once we have accepted that beliefs can be partly extrinsic, it is difficult to mount a principled argument against radical extrinsicness of divine belief. All we really have is that this extrinsicness is counterintuitive—but given God’s radical difference from creatures, we should expect God to be counterintuitive in many (infinitely many!) ways.

But I want to share a thought that has helped me be more accepting of the radical extrinsicness thesis about divine belief. There is something awkward in talking of God’s having beliefs. The much more natural way to talk is of God’s having knowledge. But knowledge is way more extrinsic in us than belief is. For you to know something, that something has to be true. So what you know depends very heavily on the external world. You know that your car is in the garage in part precisely in virtue of the fact that your car is in the garage. If your car weren’t in the garage, you wouldn’t have this knowledge.

In us, belief and knowledge are separable. Belief is much more of an intrinsic state, while knowledge is much more of an extrinsic one. When we know something outside ourselves, what makes it be the case that we know it is both a state of belief and a state of the external world. This separation makes error possible: it is possible to have the belief without the external world matching up.

But in a being that is epistemically perfect, there is no possibility of belief without knowledge. I want to suggest the plausibility of this thesis: in a being that epistemically perfect, there is not even a metaphysical separation between knowledge and belief. For such a being, to believe is to know. But knowledge of contingent external states of affairs is significantly extrinsic. So if to believe for such a being is to know, then we would expect beliefs about contingent external states of affairs to be significantly extrinsic as well.

In other words, the extrinsicness of belief that divine simplicity requires matches up with an extrinsicness that is quite plausible given considerations of the perfection of divine epistemology.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

Measuring rods

In his popular book on relativity theory, Einstein says that distance is just what measuring rods measure. I am having a hard time making sense of this in Einstein’s operationalist setting.

Either Einstein is talking of real measuring rods or idealized ones. If real ones, then it’s false. If I move a measuring rod from one location to another, its length changes, not for relativistic reasons, but simply because the acceleration causes some shock to it, resulting in a distortion in its shape and dimensions, or because of chemical changes as the rod ages. But if he’s talking about idealized rods, then I think we cannot specify the relevant kind of idealization without making circular use of dimensions—relevantly idealized rods are ones that don’t change their dimensions in the relevant circumstances.

If one drops Einstein’s operationalism, one can make perfect sense of what he says. We can say that distance is the most natural of the quantities that are reliably and to a high degree of approximation measured by measuring rods. But this depends on a metaphysics of naturalness: it’s not a purely operational definition.

Wednesday, July 21, 2021

Verifiability

I’ve been reading Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic, and been struck by how hard it is define verifiability, which is crucial since Ayer thinks that statements are meaningful if and only if they are verifiable or analytic (or, I suppose, denials of analytic statements, though oddly he doesn’t mention that possibility). Ayer rightly notes that we don’t want verifiability to mean conclusive verifiability. In the body of the text, he offers three criteria for the (weak) verifiability of p, apparently without realizing they are quite different:

it is possible for an experience to “make [p] probable”

a possible observation would be “relevant to the determination of [p’s] truth or falsehood”

together with some additional premises it entails an observation statement that cannot be derived from the premises alone.

In the 1946 introduction, he realizes that (3) makes every proposition verifiable (just make the additional premise be “if p, then o” for any observation statement o) and offers this:

- a statement is directly verifiable if it is an observation statement or if conjoined with one or more observation statements it entails an observation statement that is not entailed by the latter observation statements,

then gives a complicated account of indirectly verifiable statements, and finally defines verifiable statements as ones that are directly or indirectly verifiable.

Here’s a curious thing: (1), (3), (4) as well as the complex account of indirect verifiability can apply to a statement p without applying to its negation. For instance, consider any crazy “metaphysical” non-verifiable statement q such as his example “the Absolute is lazy” and let o be any observation statement. Then q ∧ o satisfies (3) and (4), since it entails o by itself (and hence as conjoined with some other independent observation statement). On the other hand, the negation of q ∧ o is equivalent to ∼q ∨ ∼o and does not satisfy (3), or (4), or the indirect verifiability criterion. Similarly, q ∨ o satisfies (1), since the experience reported in o would make q ∨ o conclusively probable, but the negation does not seem to satisfy (1).

But we would expect that if a statement is meaningful so is its negation. Certainly, Ayer thinks so: non-meaningful statement are neither true nor false on his view.

Account (2) is nicely symmetric between truth and falsity, and hence escapes this worry. But it has the consequence that the conjunction of two meaningful statements can be meaningless. For again let q be any crazy non-verifiable statement, and let o be the statement “It’s bright here”. Then q ∨ o is verifiable by (1), since observing brightness is clearly relevant to the truth of the disjunction, and so is q ∨ ∼o, since observing darkness is clearly relevant. Thus, both q ∨ o and q ∨ ∼o are meaningful. But (q ∨ o)∧(q ∨ ∼o) is logically equivalent to q. Thus, either the conjunction of two meaningful statements can be meaningless, or every statement is meaningful.

Maybe the best move for the positivist is to allow that meaningfulness is not closed under negation?

Thursday, July 15, 2021

A weird escape from the Knowledge Argument?

Take Jackson’s story about Mary who grows up in a black-and-white room, but learns all the science there is, including the physics and neuroscience of color perception. One day she sees a red tomato. The point of the story is that in seeing the red tomato, she has learned something, even though she already knew all the science, so the science is not all the truth there is, and hence physicalism is false.

This story is generally told in the context of the philosophy of mind, and the conclusion drawn is that physicalism about the mind is false. But that does not actually follow without further assumptions. As far as the argument goes, perhaps Mary didn’t learn anything about herself that she didn’t already know, but has learned something about tomatoes, and so we should conclude that physicalism about tomatoes is false.

Let’s explore that possibility and see if this hole in the argument can be filled. I will assume (though I am suspicious of it) that indeed the kind of knowledge gap that Jackson identifies would imply an ontological gap. Thus, I will accept that Mary has learned what it is like to see the red of a tomato, and that the knowledge of what it is like to see the red of a tomato is not a knowledge of physical fact.

Can one say this and yet accept physicalism about the mind? The one story I can think of that would allow that is a version of Dretske’s qualia externalism: just as most of us think that the content of our thoughts is partly constituted by external facts, so too the qualitative character of our perceptions is partly constituted by external facts. But in fact for the story to work as a way of blocking the inference to non-physicalism about the mind, the qualia (understood as that in the experience that cannot be known by Mary by mere book-learning) would need to be entirely constituted by extra-mental facts.

I think this kind of qualia externalism is not all that crazy. Divine simplicity requires that all of God’s knowledge of contingent fact be partly constituted by states of affairs outside God. But it is plausible that God has something like contingent qualia: that were God to contemplate a world with unicorns, it would “look” different to God than our world. On divine simplicity, we would need to have externalism about these qualia.

That said, the above affords no escape from literal anti-physicalism about the mind. If physicalism about the mind is true, then minds are brains. But if we accept that colored things have a nonphysical component that partly constitutes the perceiver’s qualia, then brains have a nonphysical component, since brains are colored things, namely pinkish (here is a description of their color in vivo, though I cannot vouch for its accuracy).

Maybe, though, this misses the point in the debate. The typical dualist thinks that there is something different about minds and other physical things. If it turns out that minds are just brains, but that they are not physical simply because their pinkness is not entirely a physical property, that’s really not what the dualist was after. The dualist’s intuition is that there is something radically different in the human brain, something not found in a pink sunset cloud (unless it turns out that panpsychism is true!).

Maybe this works to save a more robust dualist conclusion: Plausibly, one doesn’t need a tomato to make Mary have a red sensation. All one needs is to do is to induce in her brain’s visual centers the same electrical activity as normally would result from her seeing a red tomato. And the equipment inducing that electrical activity need not be red at all.

The evanescent world of becoming

An old idea in philosophy, going back to Plato, is that things that are becoming are less beings than things that are timeless. This is a mysterious view, but I have just found that my own preferred four-dimensionalism implies a clear and unmysterious version of this view.

On my preferred four-dimensionalism, material substances are four-dimensional entities. Since they are substances, they are explanatorily prior to any parts or accidents they may have. This four-dimensionalism, thus, cannot hold that four-dimensional entities are constructed out of three-dimensional time slices, or even that the slices are somehow ontologically on par with the four-dimensional substances.

Nonetheless, it makes sense to talk of a three-dimensional time slices as a kind of derivative entity.

It may, for instance, turn out to be like the Thomist’s “virtual entities”. The Thomist does not think that the electrons that help make up my body are substances, but thinks that our scientific language can be saved: the electrons “virtually exist” in virtue of my pattern of (accidental) causal powers.

Or it might even be that three-dimensional time slices just are accidents: that the four-dimensional entity that I am has an accident corresponding to every time at which it exists, an accident which itself is the bearer of further accidents. Thus, the fact that I have a certain three-dimensional shape s at a time t could be analyzed in terms of me having an existence-at-t accident Et, and Et in turn having an s-shape accident.

Virtual entities and accidents are unmysteriously less beings than substances: for them to be is to qualify a substance.

So, now, here is a reconstruction of the Platonic insight. A lot of our ordinary talk about material substances is most straightforwardly construed as about time slices rather than four-dimensional substances. When we talk of the shape of a flower, we mean its three-dimensional shape with respect to a particular slice, and so on. Now, we identify something like the Platonic world of becoming as the world of three-dimensional time slices. These are completely evanescent entities—they exist literally only for a moment each—and their being is derivative from the being of substances.

Presentists have long complained that four-dimensional entities are not really becoming. We can embrace an aspect of that insight. There is a way in which the four-dimensional entities form a world where time is less important. Granted, they indeed are spatio temporal entities: they do exist in time as well as in space. But there is little reason to think that their very being is somehow ontologically tied to time in the way that the presenists think the world of becoming is. On the other hand, the time slices are very much time slices: their very being is tied to their temporality.

Of course, this reconstruction of the Platonic insight into a world of becoming is in the end quite unfaithful to Plato: for we, who are four-dimensional substances, end up not being in the world of becoming, though we ground it. We are almost like Kantian noumena, grounding a world of becoming phenomena.

I don't know that the standard presentist can reconstruct the Platonist insight. For the standard presentist, to be is to be at present. The only difference between eternal things and things in the world of becoming is that eternal things were and will be in the same state, while things in the world of becoming were and/or will be in a different state. This is not a difference with respect to a way of being.

Wednesday, July 14, 2021

Proper empathy

Empathy is usually understood as sharing in the feelings of others, and it is thought to be an important part of closer forms of human love.

I think there is a mistake here. Consider these cases, where Alice is a very close friend of Bob.

Alice knows that Bob’s wife has been cheating on him, but because of the confidentiality of the source of the information, she is unable to information Bob. She constantly sees Bob enjoying his marriage and delighting in thinking of his wife’s loyalty.

Last week, Bob has been informed he has a terminal disease, and is feeling the normal feelings of dread. Alice works in the medical office and has just discovered that that Bob’s file was mixed up with the file of another person of the same name, who indeed had a terminal disease and died of it two years ago, and Bob’s actual diagnosis was a clean bill of health. The office has yet to inform Bob of this.

Bob is a great fan of his local hockey team. He has just found out that the star player in a team that is to play against them has just broken a leg, and is delighted, and shares his delight with Alice.

Because Bob’s country used to be occupied by the Soviet Union, Bob has a visceral dislike of Russia. He has just learned that Russia won the Ice Hockey World Championship, and this makes him sad. He shares his sadness with Alice.

Cases 1 and 2 are cases where Bob is ignorant of the relevant facts, and cases 3 and 4 are ones where he is in the grip of a vice. But in none of the four cases is it appropriate for Alice to straightforwardly share in Bob’s feelings.

In case 1, Alice can be expected to feel badly for Bob, and her feeling badly is only accentuated by the fact that Bob doesn’t feel badly. In case 2, Alice would feel delighted for Bob, with the delight tempered by some a sadness that Bob is still feeling dread. But even that sadness would not take the form of dread. In case 3, Alice might share some of Bob’s joy that his preferred team will win, but she shouldn’t feel any delight at the player breaking a leg. Moreover, Alice should feel badly about her friend exhibiting a vicious joy. Finally, in case 4, Alice should feel badly, but not as a sharing in Bob’s sadness, but as a reaction to Bob’s ethnic prejudice. However, since she knows that the feelings are unpleasant ones for Bob, she might well have some sadness for his suffering, even if that suffering is vicious in nature.

These cases suggest to me that a good human friend:

Has a first-order share in the feelings that the friend should have (i.e., would have if they were virtuous and well-informed).

Has second-order feelings in reaction to the friend’s actual first-order feelings.

In many cases where the friend is virtuous and well-informed, the first-order sharing in the feelings the friend should have is also a first-order sharing in the feelings the friend does have.

This is a much more complex, and morally loaded, set of dispositions than empathy as usually defined. I don’t know that we have a good name for this complex set of dispositions. We might, of course, call it “proper empathy”, if we like.

Tuesday, July 13, 2021

An argument against a giant multiverse

Tariq Nazeem emailed me a really cool and simple argument against certain kinds of gigantic multiverses. I’ve tweaked the argument a little, and here it is.

Start with this, as the target of the reductio ad absurdum:

- Every metaphysically possible kind of substance exists.

But:

- It is metaphysically possible to have a substance that has the causal propensity to turn every colorable object red every second.

(Colorable objects are things are like trees and dogs, but not numbers, photons or electromagnetic fields.)

Well, it follows from (1) and (2) that:

So, there is a substance that has the causal propensity to turn every colorable object red every second.

So, every colorable object turns red every second.

But I am a colorable object that does not turn red every second. (Empirical observation)

Contradiction!

My initial objection to Nazeem’s argument was that in a typical philosophical giant multiverse theory, the multiverses exist in separate spacetimes. (I think Nazeem’s own target was a view where they were in a single spacetime, but that is a less common view.) But then I realized that there is nothing absurd about a substance affecting things that are not spatiotemporally connected to it—classical theists think God is like that. Substances have causal propensities that specify the types of things they affect and the circumstances in which they affect them, and there is nothing absurd about a specification of these things and circumstances that makes no reference to a spatiotemporal connection. Therefore, (2) is pretty plausible, notwithstanding the fact that the colorable objects might exist in other spacetimes than the substance making them red does.

A different objection to this argument is what to say about conflict. What if reality included a substance that constantly made everything colorable red and another substance that constantly made everything colorable blue? Would I then be red all over and blue all over at the same time? But that’s impossible.

I am not completely clear on what to say to this objection.

One thought is: So much the worse for our giant multiverse—there are metaphysically possible pairs of kinds of substances, like the constant-reddenner and the constant-bluer, that simply cannot both be exemplified.

But on the other hand, maybe the possibility of conflict suggests that when we fully specify the causal propensities of a substance, we need to specify how they would interact with other causal propensities. Thus, we might have a constant-reddener that in the absence of other color-setters turns everything red, but in the presence of a constant-bluer, turns everything purple. However, it seems metaphysically possible to also have an overriding-reddener which makes everything red notwithstanding whatever other things exist. Then there could also be an overriding-bluer which makes everything blue notwithstanding whatever other things exist. And again this refutes (1).

Monday, July 12, 2021

A Christian argument against divine suffering

Some Christians think that God changes and is capable of changing emotions such as suffering. Now, if God is capable of suffering, then God feels empathetic suffering whenever an evil befalls us, and does so to the extent of how bad he understand the evil to be.

The worst evil that can happen to us is to sin. God knows how bad our sin is better than any human being can. Thus, if God can suffer, he suffers compassionately for our sins. He suffers this qua God and independently of any Incarnation, more intensely than any human being can.

But if so, that undercuts one of the central points of the Incarnation, which is to allow the Second Person of the Trinity to suffer for our sins.

A view on which God is capable of emotions such as suffering makes the Incarnation and Christ’s sacrifice of the Cross rather underwhelming: God’s divine suffering would be greater than Christ’s suffering on the Cross. This is theologically unacceptable.

Online talk on privation theory of evil

Saints and faith

There are many ways of life that people claim to be virtuous. A central thesis of Aristotelian ethics is:

- The virtuous person knows what is the virtuous human form of life, at least insofar as this is relevant to her own circumstances.

She knows this by living virtuously, which enables a from-the-inside appreciation of the virtue of the virtuous life she lives. This is a mysterious thing, but it means that the virtuous person does not need to worry sceptically about the fact that other people disagree with her about this way of life being virtuous (maybe they say to her: “You should have a stronger preference for people of your country over foreigners”, and she just knows that her preference should not be stronger). These other people are not virtuous, and hence lack that from-the-inside view on what it is to live a virtuous life, and hence they are not her epistemic peers with respect to virtue.

Suppose we accept (1). Now imagine that Therese leads a kind of life L that is deeply intertwined with a particular religion R, in such a way that clearly L would be unlikely to be virtuous if R were false, but is very likely to be virtuous if R is true.

It is easy to imagine cases like this. Perhaps most religious and non-religious views other than R would object to significant aspects of L—perhaps, L includes forms of activism that R praises but most other religious and non-religious views look down on, or lacks forms of activity that most religious and non-religious views other than R think are required for a fulfilling human life. The life of a good contemplative Catholic nun is like that: most non-Catholic views will see it as a waste.

Suppose, further, that Therese is in fact virtuous. Then she knows that L is virtuous, and this gives her significant evidence that R is true because of how much L is bound up with R.

One may have a Christian worry about what I just said. What about humility? Would Therese know that she is living a virtuous life? But she might: true self-insight is compatible with humility. However, my argument does not assume that Therese knows that she is living a virtuous life. All that (1) says is that Therese knows that L is a virtuous life—but she need not know that she is in fact living out L. She knows the model of the virtuous life by living it, but she may not know that she is living it. (Aristotle wouldn’t like that.)

Now, suppose that Therese’s virtue in fact comes from God’s grace. Then Therese has a deep reason to know R on the basis of grace: the grace leads to virtue, and the virtue leads to knowledge of what is virtuous.

So, we have a model for how saints of the true religion can know the truths of their faith, because their radical forms of life are so tightly bound up with their religion that their knowledge that this way of life is virtuous (a knowledge compatible with certain ways of agonizing about whether they are in fact living that way) yields knowledge of their religion.

Can this help those of us who are not saints? I think so. It is possible to see the virtue of another’s form of life even when one does not have much virtue. And then the tight intertwining between the saint’s life of virtue and the saint’s religion provides one with evidence of the truth of their religion.

(Note the similarities to the line of thought in van Inwagen's deeply moving "Quam Dilecta".)

Is this immune to sceptical worries in the way that the virtuous person’s knowledge of the virtue of the form of life she follows is? I don’t know. I think there is room for some proper-functionalism here: we may have a faculty of recognition of a virtuous form of life.

Note, finally, that there are multiple virtuous forms of life, some less radical than others. The more radical ones are likely to be more tightly bound up with their religion, and hence provide more evidence—even if they are not necessarily more virtuous. Perhaps the difference is in how specific a religion is testified to by the virtue of the way of life. Thus, the contemplative cloistered saint’s life may give strong evidence of Catholicism, or at least of the disjunction of Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, while the life of a married saint as seen from the outside may “only” give strong evidence of Christianity.

Saturday, July 10, 2021

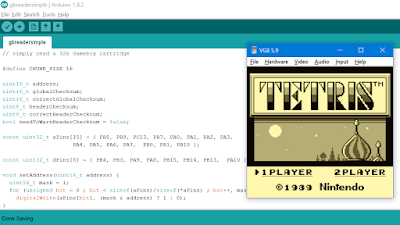

Reading a Game Boy Tetris cartridge

I saw a small rectangular PCB on the sidewalk not far from my house. It looked interesting. I left it for a couple of days in case someone lost it and returned for it. A web search showed it was the PCB from a Game Boy cartridge. Eventually, I took the PCB home, and made it a challenge to extract the data from it with only the tools I had at home and without harming the PCB (so, no soldering).

This PCB was from a ROM-only cartridge, 32K in size (I was able to identify it from the part number and photos online as likely to be Tetris), so it should have been particularly easy to read. The protocol is described here.

While the Game Boy cartridges run at 5V, the only microcontroller I had available with enough GPIOs and ready to use was an stm32f103c "black pill" which runs at 3.3V. Fortunately, it has a number of 5V-tolerant GPIOs, so there was some hope that I could run the cartridge at 5V and read it with the microcontroller.

The Game Boy I didn't have a cartridge connector, but fortunately the PCB had plated through-holes on all but two of the lines, and they fit my breadboard jumper wires very nicely. I used test clips for the remaining two lines (VCC and A0). After some detours due to connection mistakes and a possibly faulty breadboard or GPIO, I ended up with this simple setup (what a mess on the breadboard!).

1. Connect D0-D7 on the cartridge to 5V-tolerant inputs, connect A0-A14 on the cartridge to outputs, ground GND, A15 and RD (CS and RS were not connected to anything on the cartridge), and connect VCC to a power supply (it turned out that all my worries about 3.3V/5V were unnecessary: supplying 3.3V, 4.5V or 5V all worked equally well).

2. Write a 15-bit address to A0-A14. Wait a microsecond (this could be shaved down, but why bother?). Read the byte from D0-D7. Increment address. Repeat. Check the header and ROM checksums when done. Arduino code is here. (I just copied and pasted the output of that into a text file which I then processed with a simple Python script.)

It works! I now have a working Tetris in an emulator, dumped from a random PCB that had been lying on the sidewalk through torrential rains!

I've played many versions of Tetris. This one plays very nicely.

Some technical notes:

- I got advice from someone to set pulldown on the D0-D7 lines. Turns out that makes no difference.

- Cartridges that are more than 32K would need some bank switching code.

Friday, July 9, 2021

Naturalness and induction

David Lewis’s notion of the naturalness of predicates may seem at first sight like just the thing to solve Goodman’s new puzzle of induction: unlike green, grue is too unnatural for induction with respect to grue to be secure.

But this fails.

Roughly speaking, an object is green provided its emissivity or reflectivity as restricted to the visible range has a sufficiently pronounced peak around 540 nm. But in reality, it’s more complicated than that. An object’s emissivity and reflectivity might well have significantly different spectral profiles (think of a red LED that is reflectively white, as can be seen by turning it off), and one needs to define some sort of “normal conditions” combination of the two features. Describing these normal conditions will be quite complex, thereby making the concept of green be quite far from natural.

Now, it is much easier to define the concepts of emissively black (eblack) and emissively white (ewhite) than of green (or black or white, for that matter) in terms of the fundamental concepts of physics. And emeralds, we think, are eblack (since they don’t emit visible light). Then, just as Goodman defined grue as being observed before a certain date and being green and or being observed after that date and being blue, we can define eblite as existing wholly before 2100 and being eblack or existing wholly after 2100 and being ewhite. And here is the crucial thing: the concept of eblite is actually way more natural, in the Lewis sense of “natural”, than the concept of green. For the definition of eblite does not require the complexities of the normal conditions combination of emissivity and reflectivity.

Thus, if what makes induction with green work better than induction with grue is that greenness is more natural than grueness, then induction with eblite (over short-lived entities like snowflakes, say) should work even better than induction with green, since ebliteness is much more natural than grueness. But we know that we shouldn’t do induction with eblite: even though all the snowflakes we have observed are eblite, we shouldn’t assume that in the next century the snowflaskes will still be eblite (i.e., that they will start to have a white glow). Or, contrapositively, if eblite is insufficiently natural for induction, green is much too unnatural for induction.

Moreover, this points to a better story. Lewisian unnaturalness measures the complexity of a property relative to the properties that are in themselves perfectly natural. But this is unsatisfactory for epistemological purposes, since the perfectly natural properties are ones that we are far from having discovered as yet. Rather, for epistemological purposes, what we want to do is measure the complexity of a property relative to the properties that are for us perfectly natural. (This, of course, is meant to recall Aristotle’s distinction between what is more understandable in itself and what is more understandable for us.) The properties that are for us perfectly natural are the directly observable ones. And now the in itself messy property of greenness beats not only grue and eblite, but even the much more in itself natural property of eblack.

This can’t be the whole story. In more scientifically developed cases, we will have an interplay of induction with respect to for us natural properties (including ones involved in reading data off lab equipment) and in themselves natural properties.

And there is the deep puzzle of why we should trust induction with respect to what is merely for us natural. My short answer is it that it is our nature to do so, and our nature sets our epistemic norms.

Monday, July 5, 2021

Disjunctive predicates

I have found myself thinking these two thoughts, on different occasions, without ever noticing that they appear contradictory:

Other things being equal, a disjunctive predicate is less natural than a conjunctive one.

A predicate is natural to the extent that its expression in terms of perfectly natural predicates is shorter. (David Lewis)

For by (2), the predicates “has spin or mass” and “has spin and mass” are equally natural, but by (1) the disjunctive one is less natural.

There is a way out of this. In (2), we can specify that the expression is supposed to be done in terms of perfectly natural predicates and perfectly natural logical symbols. And then we can hypothesize that disjunction is defined in terms of conjunction (p ∨ q iff ∼(∼p ∧ ∼q)). Then “has spin or mass” will have the naturalness of “doesn’t have both non-spin and non-mass”, which will indeed be less natural than “has spin and mass” by (2) with the suggested modification.

Interestingly, this doesn’t quite solve the problem. For any two predicates whose expression in terms of perfectly natural predicates and perfectly natural logical symbols is countably infinite will be equally natural by the modified version of (2). And thus a countably infinite disjunction of perfectly natural predicates will be equally natural as a countably infinite conjunction of perfectly natural predicates, thereby contradicting (1) (the De Morgan expansion of the disjunctions will not change the kind of infinity we have).

Perhaps, though, we shouldn’t worry about infinite predicates too much. Maybe the real problem with the above is the question of how we are to figure out which logical symbols are perfectly natural. In truth-functional logic, is it conjunction and negation, is it negation and material conditional, is it nand, is it nor, or is it some weird 7-ary connective? My intuition goes with conjunction and negation, but I think my grounds for that are weak.

Thursday, July 1, 2021

State promotion of supernatural goods

Should a state promote supernatural goods like salvation? Here is a plausible argument, assuming the existence of supernatural goods:

Supernatural goods are good.

Any person or organization that can promote a good without detracting from any other good or promoting any bad should promote the good.

The state is an organization.

Thus, other things being equal, the state ought to promote supernatural goods when it can.

Here is a second one:

If a state can contribute to the innocent pleasure of someone (whether inside or outside the state) with no cost to anyone, it should.

Humans receiving supernatural goods gives the angels an innocent pleasure.

So, the state should promote human salvation when it can do so at no cost.

One might think that the above arguments show that we should have a theocracy. But there are two reasons why that does not follow.

First, it might be that the state is not an entity that can promote human salvation, or at least not one that can do so without cost to its primary defining tasks. This could be for reasons such as that any attempt by the state to promote supernatural goods is apt to misfire or that any state promotion of supernatural goods would have to come at the cost of natural goods (such as freedom or justice). I kind of suspect something of this sort is true, and hence that the conclusions of the arguments above are merely trivially true.

Second, and more interestingly to me, a theocratic view would hold that it is a part of the state’s special

duties of care towards its citizens that it promote their salvation. But the above arguments do not show that.

Indeed, the first argument applies to any organization, and I suspect the second one does as well. A chess club needs to promote salvation, other things being equal, perhaps every bit as much as the state. Free goods should always be promoted for all. (Worry: Am I too utilitarian here?)

Moreover, the state’s special defining duties of care are towards the state’s citizens. But it does not follow from the above arguments that the state has any special reason to promote the supernatural goods of its citizens. The arguments only show that the state, like any other organization, has a general duty to promote the supernatural goods of everyone (other things being equal).