Saturday, November 16, 2024

Reasons of identity

Tuesday, February 6, 2024

The hand and the moon

Suppose Alice tells me: “My right hand is identical with the moon.”

My first reaction will be to suppose that Alice is employing some sort of metaphor, or is using language in some unusual way. But suppose that further conversation rules out any such hypotheses. Alice is not claiming some deep pantheistic connection between things in the universe, or holding that her hand accompanies her like the moon accompanies the earth, or anything like that. She is literally claiming of the object that the typical person will identify as “Alice’s hand” that it is the very same entity as the typical person will identify as “the moon”.

I think I would be a little stymied at this point. Suppose I expressed this puzzlement to Alice, and she said: “An oracle told me that over the next decade my hand will swell to enormous proportions, and will turn hard and rocky, the exact size and shape of the moon. Then aliens will amputate the hand, put it in a giant time machine, send it back 4.5 billion years, so that it will orbit the earth for billions of years. So, you see, my hand literally is the moon.”

If Alice isn’t pulling my leg, she is insane to think this. But now I can make some sense of her communication. Yes, she really is using words in the ordinary and literal sense.

Now, to some dualist philosophers the claim that a mental state of feeling sourness is an electrochemical process in the brain is about as weird as the claim that Alice’s hand is the moon. I’ve never found this “obvious difference” argument very plausible, despite being a dualist. Thinking through my Alice story makes me a little more sympathetic to the idea that there is something incredible about the mental-physical identity claim. But I think there is an obvious difference between the hand = moon and quale = brain-state claims. The hand and the moon obviously have incompatible properties: the colors are different, the shapes are different, etc. Some sort of an explanation is needed how that can happen despite identity—say, time-travel.

The analogue would be something like this: the quale doesn’t have a shape, while the brain process does. But it doesn’t seem at all clear to me that the quale positively doesn’t have a shape. It’s just that it is not the case that it positively seems to have a shape. Imagine that qualia turned out to be nonphysical but spatially extended entities spread through regions of the brain, kind of like a ghost is a nonphysical but spatially extended entity. There is nothing obvious about the falsity of this hypothesis. And on this hypothesis, qualia would have shape.

To be honest, I suspect that even if qualia don’t have a shape, God could give them the additional properties (say, the right relation to points of space) that would give them shape.

Tuesday, August 29, 2023

Matter and distinctness of substance

According to Aristotelianism, the distinctness of two items of the same species is grounded in the distinctness of their matter. This had better be initial matter, since an item might change all of its matter as it grows.

But now imagine a seed A which grows into a tree. That tree in time produces a new seed B. The following seems possible: the chunk of matter making up A moves around in the tree, and all of it ends up forming B. Thus, A and B are made of the same matter, yet they are distinct. (If one wants them to be at the same time, one can then add a bout of time-travel.)

Probably the best response, short of giving up the distinctness-matter link (which I am happy to give up myself), is to insist that a chunk of matter cannot survive substantial change. Thus, a new seed being a new substance must have new matter. But I worry that we now have circularity. Seed B has different matter from seed A, because seed B is a new substance, which does not allow the matter to survive. But what makes it a new substance is supposed to be the difference in matter.

Thursday, February 10, 2022

Animalist functionalism

The only really plausible hope for a materialist theory of mind is functionalism. But the best theory of our identity, materialist or not, is animalism—we are animals.

Can we fit these two theories together? On its face, I think so. The thing we need to do is to make the functions defining mental life be functions of the animal, not of the brain as such. Here are three approaches:

Adopt a van Inwagen style ontology on which organisms exist but brains do not. If brains don’t exist, they don’t have functions.

Insist that some of the functions defining mental life are such that they are had by the animal as a whole and not by the brain. Probably the best bet here are the external inputs (senses) and outputs (muscles).

Modify functionalism by saying that mental properties are properties of an organism with such-and-such functional roles.

I think option 2 has some special difficulties, in that it is going to be difficult to define “external” in such a way that the brain’s connections to the rest of the body don’t count as external inputs and outputs and yet we allow enough multiple realizability to make very alien intelligent life possible. One way to fix these difficulties with option 2 is to move it closer to option 3 by specifying that the external inputs and outputs must be inputs and outputs of an organism.

Options 1 and 3, as well as option 2 if the above fix is used, have the consequence that strong AI is only possible if it is embedded in a synthetic organism.

All that said, animalist functionalism is in tension with an intuition I have about an odd thought experiment. Imagine that after I got too many x-rays, my kidney mutated to allow me exhibit the kinds of functions that are involved in consciousness through the kidney (if organism-external inputs and outputs are required, we can suppose that the kidney gets some external senses, such as a temperature sense, and some external outputs, maybe by producing radio waves, which help me in some way) in addition to the usual way through the brain, and without any significant interaction with the brain’s computation. So I am now doing sophisticated computation in my kidney of a sort that should yield consciousness. On animalist functionalism, I should now have two streams of consciousness: one because of how I function via the brain and another because of how I function via the mutant kidney. But my intuition is that in fact I would not be conscious via the kidney. If there were two streams of consciousness in this situation (which I am not confident of), only one would be mine. And that doesn’t fit with animalist functionalism (though it fits fine with non-animalist functionalism, as well as with animalist dualism, since the dualist can say that the kidney’s functioning is zombie-like).

Given that functionalism is the only really good hope we have right now for a materialist theory of mind, if my intuition about the mutant kidney is correct, this suggests that animalism provides evidence against materialism.

Friday, October 1, 2021

Musings on personal qualitative identity

Consider the popular concept of “identity”, in the sense of what one “identifies with/as”. Let’s call this “personal qualitative identity”. We can think of someone’s personal qualitative identity as a plurality of properties that the person correctly takes themselves to have and that are important, in a way that needs explication, to the person’s image of themselves.

There are a few analytic quibbles we could ask about what I just said. Couldn’t someone have properties they do not actually have as part of their identity? Surely there are lots of people who have excellences of various sorts at the heart of their self-image but lack these excellences. I don’t want to count mistakenly self-attributed properties as part of a person’s identity, because there is a kind of respect we have towards another’s personal qualitative identity that requires it to be factive. In these cases, maybe I would say that the person’s taking themselves to have the excellences is a part of their identity, but not the actual possession of the excellences.

In an opposed criticism, one might want to require the person to know that they have the properties, and not merely to correctly think they have them. But that is asking for too much. Suppose Alice identifies as ethnically Slovak, on the basis of misreading the handwriting on an old geneological document that actually said she was Slovenian. But suppose the document was wrong, and Alice in fact is Slovak rather than Slovenian. Surely it is correct to say that being Slovak is a part of her identity, even though Alice does not know that she is Slovak.

But the really central and difficult thing in the concept of personal qualitative identity is the kind of “self-identificational” importance that the person attaches to them. We have plenty of properties that we correctly believe, and even know, ourselves to have, but which lack the kind of first-person importance that makes them a part of the personal qualitative identity. There is a contradiction in saying: “It is a part of my (personal qualitative) identity that I am F, but I don’t care about being F.”

In particular, the properties that are a part of the personal qualitative identity enjoy an important role in motivating the person’s actions. Of course, any property one takes oneself to have can motivate action. I don’t much care that my eyes are blue, but my self-attribution of the blueness of my eyes motivates me to write “blue” under “eye color” on government forms. But the properties that are a part of the personal qualitative identity enter into one’s motivations more often, in wider range of contexts, and in a way more significant to oneself.

There is an ambiguity here, though. When one is motivated to act a certain way by a property in one’s identity, is one motivated by the fact that one has the property or by the fact that one identifies with that property? I want to suggest that the right answer should often be the first-order one. It is my duty as a parent to provide for my children, and I identify with my having that duty. But whether I identify with having that duty or not is irrelevant to the reason-giving force of that duty: if I didn’t identify with that duty, I would be just as obligated by it. Indeed, it seems to me to be a failure when I am moved not by my duty but by my identification with the duty. The thought “this is my duty” can be a healthy thought, but adding “and I identify as having it” is morally a thought too many, though sometimes, morally deficient as we are, we need the kick in the behind that the extra thought provides.

In fact, I think there is an interesting moral danger that I think has not been much talked about. If the property F is in my personal qualitative identity, then I also have the higher order property IF of having F in my identity. Logically speaking, this higher order property may or may not itself be a part of my identity. While in some cases it may be appropriate for IF to be a part of my identity in addition to F, in most if not all of those cases, IF should be a less central part of my identity than F, and in many cases it should not be a part of my identity at all. This is because the actual rational motivational force is often largely exhausted by my one’s having F, while a focus on IF adds an illusion of additional rational force.

In general, I think that it is important to be critical about our personal qualitative identities. There are substantive and personally important normative questions about which of one’s properties should enter into the identity. A failing I know myself to have is that I end up promoting generalizations about myself into parts of my personal qualitative identity by having them play too strong a motivational role. That “I am the kind of person who ϕs” should not play much of a role in my deliberations. What matters is whether ϕing, on a given occasion, is a good or a bad thing. Yet I find myself often deciding things on the basis of being, or not being, a certain kind of person. That's deciding on the basis of navel-gazing.

I find the following norm appealing: a property F should be a part of my identity if and only if independently of my attitude to F, my having F has significant rational importance to a broad range of my deliberations. But this austere norm is probably too austere.

Wednesday, October 30, 2019

1+1=3 or 2+2=4

On numerical-sameness-without-identity views, two entities that share their matter count as one when we are counting objects.

Here is a curious consequence. Suppose I have a statue of Plato made of bronze with the nose broken off and lost. I make up a batch of playdough, sculpt a nose out of it and stick it on. The statue of Plato survives the restoration, and a new thing has been added, a nose. But now notice that I have three things, counting by sameness:

The statue of Plato

The lump of bronze

The lump of playdough.

Yet I only added one thing, the lump of playdough or the nose that is numerically the same (without being identical) as it. So, it seems, 1+1=3.

Now, it is perfectly normal to have cases where by adding one thing to another I create an extra thing. Thus, I could have a lump of bronze and a lump of playdough and they could come together to form a statue, with neither lump being a statue on its own. A new entity can be created by the conjoining of old entities. But that’s not what happens in the case of the statue of Plato. I haven’t created a new entity. The statue was already there at the outset. And I added one thing.

Maybe, though, what should be said is this: I did create a new thing, a lump of bronze-and-playdough. This thing didn’t exist before. It is now numerically the same as the statue of Plato, which isn’t new, but it is still itself a new thing. I am sceptical, however, whether the lump of bronze-and-playdough deserves a place in our ontology. We have unification qua statue, but qua lump it’s a mere heap.

Suppose we do allow, however, that I created a lump of bronze-and-playdough. Then we get another strange consequence. After the restoration, counting by sameness:

There are two things that I created: the nose and the lump of bronze-and-playdough

There are two things that I didn’t create: the statue of Plato and the lump of bronze.

But there are only three things. Which makes it sound like 2+2=3. That’s perhaps not quite fair, but it does seem strange.

Tuesday, October 29, 2019

Sameness without identity

Mike Rea’s numerical-sameness-without-identity solution to the problem of material constitution holds that the statue and the lump have numerical sameness but do not have identity. Rea explicitly says that numerical sameness implies sharing of all parts but not identity.

Does Rea here mean: sharing of all parts, proper or improper? It had better not be so. For improper parthood is transitive.

Proposition. If improper parthood is transitive and x and y share all their parts (proper and improper), then x = y.

Proof: But suppose that x and y share all parts. Then since x is a part of x, x is a part of y, and since y is a part of y, y is a part of x. Moreover, if x ≠ y, then x is a proper part of y and y is a proper part of x. Hence by transitivity, x would be a proper part of x, which is absurd, so we cannot have x ≠ y. □

So let’s assume charitably that Rea means the sharing of all proper parts. This is perhaps coherent, but it doesn’t allow Rea to preserve common sense in Tibbles/Tib cases. Suppose Tibbles the cat loses everything below the neck and becomes reduced to a head in a life support unit. Call the head “Head”. Then Head is a proper part of Tibbles. The two are not identical: the modal properties of heads and cats are different. (Cats can have normal tails; heads can’t.) This is precisely the kind of case where Rea’s sameness without identity mechanism should apply, so that Head and Tibbles are numerically the same without identity. But Tibbles has Head as a proper part and Head does not have Head as a proper part. But that means Tibbles and Head do not share all their proper parts.

Here may be what Rea should say: if x and y are numerically the same, then any part of the one is numerically the same as a part of the other. This does, however, have the cost that the sharing-of-parts condition now cannot be understood by someone who doesn’t already understand sameness without identity.

Friday, September 15, 2017

Four-dimensionalism and caring about identity

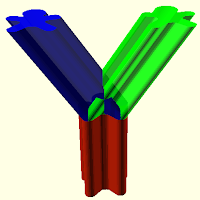

This view seems to me to be deeply implausible from a four-dimensional point of view. I am a four-dimensional thing. This four-dimensional thing should prudentially care about what happens to it, and only about what happens to it. The red-and-black four-dimensional thing in the diagram here (up/down represents time; one spatial dimension is omitted) should care about what happens to the red-and-black four-dimensional thing, all along its temporal trunk. This judgment seems completely unaffected by learning that the dark slice represents an episode of amnesia, and that no memories pass from the bottom half to the upper half.

Or take a case of symmetric fission, and suppose that the facts of identity are such that I am the red four-dimensional thing in the diagram on the right. Suppose both branches have full memories of what happens before the fission event. If I am the red four-dimensional thing, I should prudentially care about what happens to the red four-dimensional thing. What happens to the green thing on the right is irrelevant, even if it happens to have in it memories of the pre-split portion of me.

Or take a case of symmetric fission, and suppose that the facts of identity are such that I am the red four-dimensional thing in the diagram on the right. Suppose both branches have full memories of what happens before the fission event. If I am the red four-dimensional thing, I should prudentially care about what happens to the red four-dimensional thing. What happens to the green thing on the right is irrelevant, even if it happens to have in it memories of the pre-split portion of me.The same is true if the correct account of identity in fission is Parfit’s account, on which one perishes in a split. On this account, if I am the red four-dimensional person in the diagram on the left, surely I should prudentially care only about what happens to the red four-dimensional thing; if I am the green person, I should prudentially care only about what happens to the green one; and if I am the blue one, I should prudentially care only about what happens to the blue one. The fact that both the green and the blue people remember what happened to the red person neither make the green and blue people responsible for what the red person did nor make it prudent for the red person to care about what happens to the green and blue people.

This four-dimensional way of thinking just isn’t how the discussion is normally phrased. The discussion is normally framed in terms of us finding ourselves at some time—perhaps a time before the split in the last diagram—and wondering which future states we should care about. The usual framing is implicitly three-dimensionalist: what should I, a three-dimensional thing at this time, prudentially care about?

But there is an obvious response to my line of thought. My line of thought makes it seem like I am transtemporally caring about what happens. But that’s not right, not even if four-dimensionalism is true. Even if I am four-dimensional, my cares occur at slices. So on four-dimensionalism, the real question isn’t what I, the four-dimensional entity, should prudentially care about, but what my three-dimensional slices, existent at different times, should care about. And once put that way, the obviousness of the fact that if I am the red thing, I should care about what happens to the red thing disappears. For it is not obvious that a slice of the red thing should care only about what happens to other slices of the red thing. Indeed, it is quite compelling to think that the psychological connections between slices A and B matter more than the fact that A and B are in fact both parts of the same entity. (Compare: the psychological connections between me and you would matter more than the fact that you and I are both parts of the same nation, say.) The correct picture is the one here, where the question is whether the opaque red slice should care about the opaque green and opaque blue slices.

In fact, in this four-dimensionalist context, it’s not quite correct to put the Parfit view as “psychological connections matter more than identity”. For identity doesn’t obtain between different slices. Rather, what obtains is co-parthood, an obviously less significant relation.

However, this response to me depends on a very common but wrongheaded version of four-dimensionalism. It is I that care, feel and think at different times. My slices don’t care, don’t feel and don’t think. Otherwise, there will be too many carers, feelers and thinkers. If one must have slices in the picture (and I don’t know that that is so), the slices might engage in activities that ground my caring, my feeling and my thinking. But these grounding activities are not caring, feeling or thinking. Similarly, the slices are not responsive to reasons: I am responsive to reasons. The slices might engage in activity that grounds my responsiveness to reasons, but that’s all.

So the question is what cares I prudentially should have at different times. And the answer is obvious: they should be cares about what happens to me at different times.

About the graphics: The images are generated using mikicon’s CC-by-3.0 licensed Gingerbread icon from the Noun Project, exported through this Inkscape plugin and turned into an OpenSCAD program (you will also need my tubemesh library).

Tuesday, December 27, 2016

Some weird languages

Platonism would allow one to reduce the number of predicates to a single multigrade predicate Instantiates(x1, ..., xn, p), by introducing a name p for every property. The resulting language could have one fundamental quantifier ∃, one fundamental predicate Instantiates(x1, ..., xn, p), and lots of names. One could then introduce a “for a, which exists” existential quantifier ∃a in place of every name a, and get a language with one fundamental multigrade predicate, Instantiates(x1, ..., xn, p), and lots of fundamental quantifiers. In this language, we could say that Jim is tall as follows: ∃Jimx Instantiates(x, tallness).

On the other hand, once we allow for a large plurality of quantifiers we could reduce the number of predicates to one in a different way by introducing a new n-ary existential quantifier ∃F(x1, …, xn) (with the corresponding ∀P defined by De Morgan duality) in place of each n-ary predicate F other than identity. The remaining fundamental predicate is identity. Then instead of saying F(a), one would say ∃Fx(x = a). One could then remove names from the language by introducing quantifiers for them as before. The resulting language would have many fundamental quantifiers, but only only one fundamental binary predicate, identity. In this language we would say that Jim is tall as follows: ∃Jimx∃Tally(x = y).

We have two languages, in each of which there is one fundamental predicate and many quantifiers. In the Platonic language, the fundamental predicate is multigrade but the quantifiers are all unary. In the identity language, the fundamental predicate is binary but the quantifiers have many arities.

And of course we have standard First Order Logic: one fundamental quantifier (say, ∃), many predicates and many names. We can then get rid of names by introducing an IsX(x) unary predicate for each name X. The resulting language has one quantifier and many predicates.

So in our search for fundamental parsimony in our language we have a choice:

- one quantifier and many predicates

- one predicate and many quantifiers.

Are these more parsimonious than many quantifiers and many predicates? I think so: for if there is only one quantifier or only one predicate, then we can collapse levels—to be a (fundamental) quantifier just is to be ∃ and to be a (fundamental) predicate just is to be Instantiates or identity.

I wonder what metaphysical case one could make for some of these weird fundamental language proposals.

Tuesday, May 17, 2016

Relative identity and relative shape

Take a classic case of relative-identity. At time 1, we have a lump of clay, Lumpy1, that is formed into a statue of a horse, a statue I will call "Bucephalus". At time 2, the lump continues to exist as Lumpy2, but is reformed into into a statue of a big man, a statue I will call "Goliath". Then Lumpy1 is the same lump as Lumpy2, Lumpy1 is the statue as Bucephalus, Lumpy2 is the same statue as Goliath, but it does not follow that Lumpy1 is the same statue as Lumpy2, since we only have transitivity of relative identity when we keep the kind fixed.

Now suppose a four-dimensionalism that says that ordinary objects are four-dimensional (no further commitments on temporal parts, etc.). Then it seems we have a very odd thing. Lumpy1 the lump has a different shape and size from Bucephalus the statue. For Lumpy1 the lump is extended temporally up to and including at least time 2, while Bucephalus the statue does not extend temporally up to time 2. So shape and size are kind-relative. As a lump, Lumpy1 has one four-dimensional shape and size. As a statue, it's Bucephalus and it has a different four-dimensional shape and size. The causal powers are different, too. Lumpy1 can still be seen at time 2, while Bucephalus can no longer be seen then (except in photographs). So the causal powers of a thing are kind-relative, too. Moreover, this kind of thing happens routinely--it's not a miracle as when Christ is omnipresent qua God but only in Jerusalem qua human. It seems implausible that we would have routine kind-relative variation of size and shape.

This makes relative identity not so plausible given four-dimensionalism. But four-dimensionalism (in the weak sense I'm using) is clearly true. :-)

Relative identity and relative parthood

Advocates of relative identity say that identity is always relative to a kind. This seems to have an interesting and underappreciated consequence: If there is such a thing as parthood, it's relative to a kind too. For:

- Necessarily: x=y if and only if x is a part of y and y is a part of x.

Is it crazy to think parthood is relative to a kind? Maybe not. Consider classic apparent counterexamples to the transitivity of parthood like: My right foot is a part of me and I am part of the Admissions Committee, but my right foot is not a part of the Admissions Committee. Well, we could say: my right foot is a part of me qua organism, while I am a part of the Admissions Committee qua organization. It's unsurprising that can't chain "___ is a part of ___ qua F" and "___ is a part of ___ qua G" together. On the other hand, perhaps we can say that my right foot is a part of me qua physical object and I am a part of the Admissions Committee qua physical object, so my right foot is a part of the Admissions Committee qua physical object. That sounds just right! So the kind-relativity of parthood seems to be a helpful thesis, at least in this regard.

Still, having to say that parthood is kind-relative is additional baggage for the relative identity theorist to take on board. Can she escape from the weight of that load? Maybe. She could say that diachronic identity is relative but synchronic identity is absolute. If she says that, then she could say that (1) holds but only for synchronic identity and synchronic (three-dimensionalist) parthood. (I think, though, that one shouldn't make diachronic identity be any different from synchronic identity. They are both, just, identity.)

Friday, March 21, 2014

The human animal and the cerebrum

Suppose your cerebrum was removed from your skull and placed in a vat in such a way that its neural functioning continued. So then where are you: Are you in the vat, or where the cerebrum-less body with heartbeat and breathing is?

Most people say you're in the vat. So persons go with their cerebra. But the animal, it seems, stays behind—the cerebrum-less body is the same animal as before. So, persons aren't animals, goes the argument.

I think the animal goes with the cerebrum. Here's a heuristic.

- Typically, if an organism of kind K is divided into two parts A and B that retain much of their function, and the flourishing of an organism of kind K is to a significantly greater degree constituted by the functioning of A than that of B, then the organism survives as A rather than as B.

Another related heuristic:

- Typically, if an organism of kind K is divided into two parts A and B that retain much of their function, and B's functioning is significantly more teleologically directed to the support of A than the other way around, then the organism survives as A rather than as B.

My heart exists largely for the sake of the rest of my body, while it is false to say that the rest of my body exists largely for the sake of my heart. So if I am divided into a heart and the rest of me, as long as the rest of me continues to function (say, due to a mechanical pump circulating blood), I go with the rest of me, not the heart. But while the cerebrum does work for the survival of the rest of my body, it is much more the case that the rest of the body works for the survival of the cerebrum.

There may also be a control heuristic, but I don't know how to formulate it.

Wednesday, February 5, 2014

Might "animal" be a stage term?

Consider this argument:

- It is possible for me to exist disembodied.

- It is not possible for an animal to exist disembodied.

- So, I am not an animal.

- It is possible for Tom Brady to exist disembodied.

- It is not possible for a football player to exist disembodied.

- So, Tom Brady is not a football player.

- It is not possible for someone who is presently a football player to exist disembodied at any time.

- It is not possible for someone to exist disembodied while being a football player.

Why not draw the same conclusion from the first argument? Granted (I am not sure of this) one can't be disembodied while being an animal. But why can't someone who is an animal at one time be disembodied at another time, ceasing to be an animal then? Then "animal" would be a stage term. (It could even be the case that "animal" is a stage term while "person" isn't.)

If animalism is the claim that we are animals, then this would be compatible with animalism. One couldn't, however, straightforwardly say that we are essentially animals. But one could say that it is an essential property of beings like us that they begin their existence as animals, or at least (maybe God could create someone already in the disembodied stage?) that they normally do so.

One could say that these are claims about all animals or just about rational ones. Maybe only some animals—say, the rational ones—have the capability of becoming disembodied souls.

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Psychological theories of personal identity and transworld identity

On psychological theories of personal identity, personal identity is constituted by diachronic psychological relations, such as memory or concern. As it stands, the theory is silent on what constitutes transworld identity: what makes person x in world w1 be the same as person y in world w2. But let us think about what could be send in the vein of psychological theories about transworld identity.

Perhaps we could say that x in w1 is the same as y in w2 provided that x and y have the same earliest psychological states. But now sameness of psychological states is either type-sameness or token-sameness. If it's type-sameness, then we get the absurd conclusion that had your earliest psychological states been just like mine, you would have been me. Moreover, it is surely possible to have a world that contains two people who have the same earliest types of psychological states. But those two people aren't identity.

On the other hand, if we are talking of token-sameness, then we seem to get circularity, since the token-sameness of mental states presupposes the identity of the bearers. But there is a way out of that difficulty for naturalists. The naturalist can say that the mental states are constituted by some underlying physical states of a brain or organism. And she can then say that token-sameness of mental states is defined in terms of the token-sameness of the underlying physical states. This leads to the not implausible conclusion that you couldn't have started your existence with a different brain or organism.

But I think any stories in terms of initial psychological states face the serious difficulty that it is surely possible for me to have been raised completely differently and to have had different initial psychological states. This is obvious if the initial psychological states that count are states of me after the development of the sorts of cognitive functions that many (but not me) take to be definitive of personhood: for such functions develop after about one year of age, and surely I could have had a different life at that point.

In fact this line of thought suggests that no psychological-type relation is necessary for transworld identity. But if no psychological-type relation is necessary for transworld identity, why think it's necessary for intraworld identity?

Sunday, February 17, 2013

The Incarnation, personal identity and time

On the traditional understanding of Christ's Incarnation, Christ has two minds—a human mind and a divine mind—even though he is one person. The two minds have different mental states. In his divine mind, which he has in common with the Father and the Holy Spirit, Christ is omniscient. In his human mind, he is not. There are things that he knows with his divine mind which he does not even believe with his human being, because there are thoughts conceptually beyond the ability of the human mind to think. Yet how could one have two incompatible collections of mental contents like that, and yet be one person? Likewise, Christ divinely wills certain things, say that all reality continue to exist, which he presumably does not will humanly.

But suppose that the past is real—i.e., that either eternalism or growing block is true. Then I, too, am a person with incompatible collections of mental contents. At age 2, I did not even have the concepts needed to grasp the Pythagorean Theorem. Now I know the Theorem to be true. Yet it is the very same person we are talking about here. So the very same person has two incompatible collections of mental states.

But there seems to be a difference. I don't know the Pythagorean theorem at age 2, but I know the Pythagorean theorem at age 40. There is no problem here. But Christ at the same time knows and doesn't know some propositions.

Actually, though, it's not clear that it makes sense to say that Christ at the same time knows and doesn't know some propositions. In his divine nature, Christ is timeless. So perhaps we should say that Christ at age 30 doesn't know p, but Christ timelessly (or "at eternity") knows p.

But that's not exactly my point. The point I want to make is a little subtler and would hold even if God was in time rather than being timeless: the adverbial modifiers "at age 2" and "at age 40" work rather like the modifiers "as human" and "as God". Just as there is no contradiction between my knowing p at age 40 and not knowing p at age 2 (or vice versa), there is no contradiction between Christ's knowing p as God and not knowing it as human.

There is a sense in which the succession of time multiplies our wills and minds: we pursue and believe different things at different times. While I don't want to say that we have literally different wills and minds at different times, the diachronic distribution of our pursuits and beliefs shows that personal identity does not require any strong unity of apperception. At most, according to some theorists, there need to be some interconnections, like those of memory. And other theorists—the ones who are right!—don't even think connections of memory are needed for personal identity.

The analogy between times (in our case) and natures (in the case of Christ) is of course only an analogy. But I think it is potentially a fruitful and underexplored one. Notice that the analogy extends beyond the mental life. Just as Christ is both omnipotent (as God) and weak (as a man), I am both relatively strong (now) and helpless (in infancy).

How well the analogy runs will depend on the theory of persistence over time that one is thinking about. I am inclined to either endurantism or stageless worm theory, so those are the theories on which the above intuitions are based. But one will get a different picture—perhaps no longer orthodox—if one bases the analogy on perdurantism.

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

Leibniz, bodies and phenomena

Leibniz tells us that bodies are phenomena. He also tells us that phenomena are modes of monads. Now, the modes of monads are appetites and perceptions. But appetites and perceptions are identity-dependent on the monad that they are appetites and perceptions of. Your appetite or perception may be very much like mine, but it is numerically distinct from mine. But this seems to imply that the moon you see and the moon I see are numerically distinct. For the moon you see is a mode of you, and hence identity-dependent on you, while the moon I see is a mode of me, and hence not numerically distinct with the moon that is identity-dependent on you.

Something must go. The identity dependence of modes on the monad is central to Leibniz's argument against inter-modal causation: he insists that the same mode cannot have a leg in each of two monads. My suggestion is that what Leibniz should say, and maybe what he really thinks, is that real phenomena, like the moon, aren't modes of monads in the narrow sense that implies identity dependence, but are grounded in monads, and in that sense are modes of monads in the broad sense. Consider "the committee's opinion." This is grounded in the committee members' minds, but it is not identity-dependent on any one committee member: individual committee members can change their view while the committee is still "of the same mind."

Here is one way to make this go. The moon is a phenomenon and it has a two-fold ground. One part of the ground are monads having "lunar perceivings", like the one I had last night when looking through the telescope, and like the one I am now, according to Leibniz, unconsciously having. But the moon isn't just a lunar perceivings, because your lunar perceiving is distinct from my lunar perceiving. The other part of the ground is what unifies the lunar perceivings in different monads, and that is the monads that are elements (in Robert Adams' phraseology) of the moon. Your lunar perceiving represents the same lunar monads as my lunar perceiving does.

For Leibniz, as for Aristotle, being and unity are interchangeable. To have being, bodies need a source of unity. On this reading, there are two sources of unity in the moon: first, the perception of a monad, say you or me, unifies the many lunar monads that are being perceived; second, the lunar monads unify the perceptions of the many monads. There is no vicious circularity here.

This significantly qualifies Leibniz's alleged idealism. It sounds idealist to say that bodies are phenomena. But they aren't just any phenomena, they are "well founded" phenomena (to use Leibniz's phrase), and a part of what constitutes them into the self-identical phenomena that they are is the monads that are appearing in the appearance.

The above brings together ideas I got from at least two of our graduate students. Another move suggested by one of them is to take the unification of the lunar perceivings to happen through the complete individual concept of the moon which is confusedly found in all of the lunar perceivings. I think this, too, is a possible reading of Leibniz, but I think it makes for poorer philosophy, since I don't think there is any complete individual concept of the moon found in all lunar perceivings, except in the way that the concepts of causes are, by essentiality of origins, found in the effects.

Sunday, December 26, 2010

Hierarchy and unity

Vatican II gives a very hierarchical account of unity in the Church:

This collegial union is apparent also in the mutual relations of the individual bishops with particular churches and with the universal Church. The Roman Pontiff, as the successor of Peter, is the perpetual and visible principle and foundation [principium et fundamentum] of unity of both the bishops and of the faithful. The individual bishops, however, are the visible principle and foundation of unity in their particular churches, fashioned after the model of the universal Church, in and from which churches comes into being the one and only Catholic Church. For this reason the individual bishops represent each his own church, but all of them together and with the Pope represent the entire Church in the bond of peace, love and unity.(Lumen Gentium 23)The unity of each local Church is grounded in the one local bishop, and the unity of the bishops is grounded in the one pope. Unity at each level comes not from mutual agreement, but from a subordination to a single individual who serves as the principle (principium; recall the archai of Greek thought) of unity. This principle of unity has authority, as the preceding section of the text tells us. In the case of the bishops, this is an authority dependent on union with the pope. (The Council is speaking synchronically. One might also add a diachronic element whereby the popes are unified by Christ, whose vicars they are.)

A hierarchical model of unity is perhaps not fashionable, but it neatly avoids circularity problems. Suppose, for instance, we talk of the unity of a non-hierarchical group in terms of the mutual agreement of the members on some goals. But for this to be a genuine unity, the agreement of the members cannot simply be coincidental. Many people have discovered for themselves that cutting across a corner can save walking time (a consequence of Pythagoras' theorem and the inequality a2+b2<(a+b)2 for positive a and b), but their agreement is merely coincidental and they do not form a genuine unified group. For mutual agreement to constitute people into a genuine group, people must agree in pursuing the group's goals at least in part because they are the goals of the group. But that, obviously, presents a vicious regress: for the group must already eist for people to pursue its goals.

The problem is alleviated in the case of a hierarchical unity. A simple case is where one person offers to be an authority, and others agree to be under her authority. They are united not by their mutual agreement, but by all subordinating themselves to the authority of the founder. A somewhat more complex case is where several people come together and agree to select a leader by some procedure. In that case, they are still united, but now by a potential subordination rather than an actual one. This is like the case of the Church after a pope has died and another has yet to be elected. And of course one may have more complex hierarchies, with multiple persons owed obedience, either collectively or in different respects.

This, I think, helps shed some light on Paul's need to add a call for a special asymmetrical submission in the family—"Wives, be subject to your husbands, as to the Lord" (Eph. 5:22)—right after his call for symmetrical submission among Christians: "Be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ" (Eph. 5:21). Symmetrical submission is insufficient for genuine group unity. And while, of course, everyone in a family is subject to Christ, that subjection does not suffice to unite the family as a family, since subjection to Christ equally unites two members of one Christian family as it does members of different Christian families. The need for asymmetrical authority is not just there for the sake of practical coordination, but helps unite the family as one.

In these kinds of cases, it is not that those under authority are there for the benefit of the one in authority. That is the pagan model of authority that Jesus condemns in Matthew 20:25. Rather, the principle of unity fulfills a need for unity among those who are unified, serves by unifying.

There is a variety of patterns here. In some cases, the individual in authority is replaceable. In others, there is no such replaceability. In most of the cases I can think of there is in some important respect an equality between the one in authority and those falling under the authority—this is true even in the case of Christ's lordship over the Church, since Christ did indeed become one of us. But in all cases there is an asymmetry.

Here is an interesting case. The "standard view" among orthodox Catholic bioethicists (and I think among most pro-life bioethicists in general) is that:

- Humans begin to live significantly before their brains come into existence.

- Humans no longer live when their brains have ceased all function (though their souls continue to exist).

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Diachronic Identity paper posted

I just posted a paper defending a deflationary theory of diachronic identity.

Friday, November 27, 2009

More on the deflationary account of diachronic identity

[Cross-posted from Matters of Substance.]

First, the easy version of the deflationary account. Here is a question about diachronic identity: What makes it be the case that:

- Some F0 at t0 is diachronically identical with some F1 at t1.

- There exists an x such that x is an F0 at t0 and x is an F1 at t1.

Now, the somewhat harder version, the question of analyzing diachronic identity wffs. Question: What makes it be the case that:

- x at t0 is diachronically identical with y at t1.

- x exists at t0 and x exists at t1 and y exists at t1 and x is synchronously identical at t1 with y.

If one is worried that "x exists at t" presupposes diachronic identity, consider this. What is it to exist at t? Here are some standard proposals:

- Presentism: At t: x exists.

- Perdurantism: a part of x is located within the spacelike hypersurface t.

- Eternalist endurantism: x is wholly located within the spacelike hypersurface t.

In any case, substantive accounts of diachronic identity do not clarify what it is to be located in a region of spacetime or what it is to exist at t. Substantive accounts of diachronic identity explain what it is for an object that is located in one region to exist in another region, but that still doesn't explain what it was for the object to be located in the first region. In fact, there is something really weird about substantive accounts of diachronic identity here. It would be very strange to claim to have a good account of what it is for a person who is queen of country x to also be queen of country y (for general non-identical x and y) without that account also being an account of what it is for a person to be queen of x (for a general x). Surely we all need an account of what it is for a person to be a queen of x, and once we have that, the account of what it is for the queen of country x to also be the queen of country y is just a matter of applying that account twice (and using synchronic identity to take care of the definite articles). But like the queen-identity theorist, the substantive diachronic identity theorist has an account of what it is for, say, a person who occupies R1 to also occupy R2, without having an account of what it is to occupy R1. And once we have an account of what it is to occupy R1, we get for free an account of what it is to occupy R1 and R2, at least if we have synchronic identity.

Maybe the simplest way to summarize the deflationary account is this. It is no more mysterious how it is that x at t0 is identical with y at t1 than it is how it is that x who is the Queen of England is identical with y who is the Queen of Canada.

However, the above arguments presupposed that we're dealing with entities facts about which do not wholly reduce to facts about some other entities. In the case of wholly reducible entities, my arguments fail. The reason for that is that in the case of a wholly reducible entity, what it is to exist at t will be reducible to facts about some other class of entities. For instance, for a reducible x to exist at t will not be a matter of x's instantiating some primitive located-at relations. In that case, the conceptual baggage of "exists at t" might be the same as the conceptual baggage of the substantive account of diachronic identity, and so the deflationary account may be incorrect. (I think of wholly reducible entities as akin to wholly stipulative meanings. In the case of words with wholly stipulative meanings, we might not expect deflationary accounts of truth and meaning to apply--we might want the stipulations to be expanded out, like abbreviations, before the deflationary account is applied.)

If I am right, then someone giving a substantive account of what diachronic identity for Ks consists in is committed to Ks being reducible.