Fix a sample space Ω and an algebra F events on Ω. A gamble is an F-measurable real-valued function on Ω. A credence function is a function from a F to the reals. A prevision or price function on a set of set G of gambles is just a function from G to the real numbers. A previsory method E on a set of gambles G and a set of credence functions C assigns to each credence function P ∈ C a prevision EP on G.

A previsory method on G and C has the weak domination property provided that if f and g are two gambles such as that f ≤ g everywhere on Ω, then EP(f)≤EP(g) for every f and g in G and P in C. It has the strong domination property provided that it has the weak domination property and if f < g everywhere on Ω, then EP(f)<EP(g). It has the zero property provided that EP(0)=0.

Mathematical expectation is a previsory method on the set of all bounded gambles and all probability functions. It has the zero and strong domination properties.

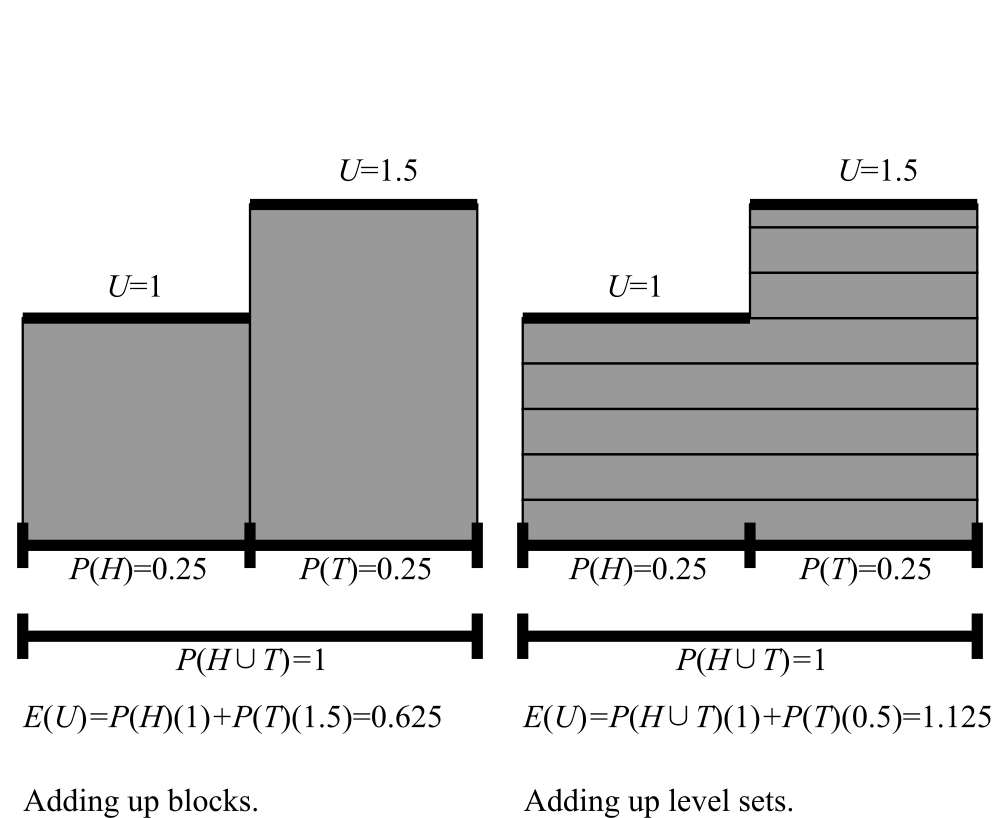

The level set integral is a previsory method on the set of all bounded gambles and all monotonic credence functions (P is monotonic iff P(⌀)=0, P(Ω)=1 and P(A)≤P(B) whenever A ⊆ B). It has the zero and weak domination properties.

The level set integral has the strong domination property on the set of weakly countably additive monotonic credence functions, where P is weakly countably additive provided that Ω cannot be written as a countable union of sets each of credence 0. If F (or Ω) is finite, we get weak countable additivity for free from monotonicity.

A previsory method E requires (permits) a gamble f given a credence P provided that EP(f)>0 (EP(f)≥0); it requires (permits) it over some set S of gambles provided that EP(f)>EP(g) (EP(f)≥Ep(g)) for every g in S.

A previsory method with the zero and weak domination properties cannot be strongly Dutch-Booked in a single wager: i.e., there is no gamble U such that U < 0 everywhere that the method requires. If it also has the strong domination property, it cannot be weakly Dutch-Booked in a single wager: there is no U such that U < 0 everywhere that the method permits.

Suppose we combine a previsory method with the following method of choosing which gambles to adopt in a sequence of offered gambles: you are required (permitted) to accept gamble g provided that EP(g1 + ... + gn + g)>EP(g1 + ... + gn) (≥, respectively) where g1 + ... + gn are the gambles already accepted. Then given the zero and weak domination properties, we cannot be strongly Dutch-Booked by a sequence of wagers, and given additionally the strong domination property, we cannot be weakly Dutch-Booked, either.

Given that level set integrals provide a non-trivial and mathematically natural previsory method with the zero and strong domination properties on a set of credence functions strictly larger than the consistent ones, Dutch-Book arguments for consistency fail.

What about epistemic utility, i.e., scoring-rule, arguments? I think these also fail. A scoring-rule assigns a number s(p, q) to a credence function p and a truth function q (i.e., a probability function whose values are always 0 or 1). Let T be truth, i.e., a function from Ω to truth functions such that T(ω)(A) if and only if ω ∈ A. Thus, T(ω) is the truth function that says “we are at ω” and we can think of s(p, T) as a gamble that measures how far p is from truth.

If E is previsory method on a set of gambles G and a set of credence functions C, then we say that s is an E-proper scoring rule provided that s(p, T) is in G for every p in C and Eps(p, T)≤Eps(q, T) for every p and q in C. We say that it is strictly proper if additionally we have strict inequality whenever p and q are different.

If E is mathematical expectation, then E-propriety and strict E-propriety are just propriety and strict propriety.

It is thought (Joyce and others) that one can make use of the concept of strictly propriety to argue for that credence functions should be consistent. This uses a domination theorem that says that if s is a strictly proper additive scoring rule, then for any inconsistent credence function p there is a consistent function q such that s(p, T(ω)) < s(q, T(ω)) for all ω. (Roughly, an additive scoring rule adds up scores point-by-point over Ω.)

However, I think the requirement of additivity is one that someone sceptical of the consistency requirement can reasonably reject. There are mathematical natural previsory methods E that apply to some inconsistent credences, such as the monotonic ones, and these can be used to define (at least under some conditions) strictly E-proper scoring rules. And the domination theory won’t apply to these rules because they won’t be additive. Indeed, that is one of the things the domination theorem shows: if C includes an inconsistent credence function and E has the strong domination property, then no strictly E-proper scoring rule is additive.

So, really, how helpful the domination theorem is for arguing for consistency depends on whether additivity is a reasonable condition to require of a scoring rule. It seems that someone who thinks that it is OK to reason with a broader set of credences than the consistent ones, and who has a natural previsory method E with the strong domination property for these credences, will just say: I think the relevant notion isn’t propriety but E-propriety, and there are no strongly E-proper scoring rules that are additive. So, additiveness is not a reasonable condition.

Are there any strongly E-proper scoring rules in such cases?

[The rest of the post is based on the mistake that E-propriety is additive and should be dismissed. See my discussion with Ian in the comments.]

Sometimes, yes.

Suppose E is previsory method with the weak domination condition on the set of all bounded gambles on Ω. Suppose that E has the scaling property that Ep(cf)=cEp(f) for any real constant c. (Level Set Integrals have scaling.) Further, assume the separability property that there is a countable set of B of bounded gambles such that for any two distinct credences p and q, there is a bounded gamble f in B such that Epf ≠ Eqf. (Level Set Integrals on a finite Ω—or on a finite field of events—have separability: just let B be all functions whose values are either 0 or 1, and note that Ep1A = p(A) where 1A is the function that is 1 on A and 0 outside it.) Finally, suppose normalization, namely that Ep1Ω = 1. (Level Set Integrals clearly have that.)

Note that given separability, scaling and normalization, there is a countable set H of bounded gambles such that if p and q are distinct, there exist f and g in H such that Ep requires f over g (i.e., Epf > Epg) and Eq does not or vice versa. To see this, let H consist of B together with all constant rational-valued functions, and note that if Epf < Eqf, then we can choose a rational number r such that r lies between Epf and Eqf, and then Ep and Eq will disagree on whether f is required over r ⋅ 1Ω.

Let H be the countable set in the above remark. By scaling, we may assume that all the gambles in H are bounded by 1. Let (f1, g1),(f2, g2),... be an enumeration of all pairs of members of H. Define sn(p, T(ω)) for a credence function p in C as follows: if Ep requires fn over gn then sn(p, T(ω)) = −fn(ω), and otherwise sn(p, T(ω)) = −gn(ω).

Note that sn is an E-proper scoring rule. For suppose that q is a different credence function from p and Epsn(p, T)>Epsn(q, T). Now there are four possibilities depending on whether Ep and Eq require fn over gn and it is easy to see that each possibility leads to a contradiction. So, we have E-propriety.

Now, let s(p, T) be Σn = 1∞ 2−nsn(p, T). The sum of E-proper scoring rules is E-proper, so this is an E-proper scoring rule.

What about strict propriety? Suppose that p and q are credence functions in C and Eps(p, T)≤Eps(q, T). By the E-propriety of each of the sn, we must have Epsn(p, T)=Epsn(q, T) for all n. Thus, for all pairs of members of H, the requirements of Ep and Eq must agree, and by choice of H, p and q cannot be different.